Shafer Grist Mill History

by Rob Jacoby (2007)

I. Property Description

The Stillwater Grist Mill is a superlative example of 19th century American mill design and is an important representation of a rural industry that contributed to the development and sustenance of an agricultural community in northwestern New Jersey (Figure 1).

Located in Stillwater Township, the mill drew water from the Paulinskill River via a raceway to drive its turbine-powered machinery. Built in 1844 by Rev. Casper Schaeffer upon the burned ruins of his previous mill,[1] the 3 ½-story, side-gabled building was situated on the village main street, set among residential dwellings, commercial establishments, and workshops (Figure 2).

The mill, measuring 40 x 36 feet, was constructed of locally quarried limestone, some of which was salvaged from the remains of the earlier mill. Large dressed stones comprise the two-foot thick walls of the ground floor, with smaller, more irregularly shaped stones used for the upper stories (Figure 3).

The upper stories were faced with lime-based plaster stucco, adding a protective cladding to the walls and giving the mill a distinctive appearance. Projecting from the upper story is a large gabled dormer with entryway that supported the exterior pulley used for conveying raw grains into the mill and processed flour out onto wagons. Separate entryways below the hoist overhang provide access to the second and third floors, while doorways into the ground floor are located at the front and rear of the mill (Figure 4). A mix of six-over-six and two-over-two sash windows, are symmetrically arrayed across the four elevations (Figure 5). Ground floor arches, front and rear, provided access and exit of the raceway for the mill’s waterpower source (Figure 6).

The mill property has historically contained 18 acres of alluvial terrace along the Paulinskill River, and includes the headrace, tailrace, flume, mill building, and a miller’s house situated on the riverbank. The headrace extends for about ¼-mile upstream where a diversion dam directed water to the race from the river. As water in the race approached the mill, an iron trash rack prevented debris from entering the flume and clogging or damaging the turbine (Figure 7).

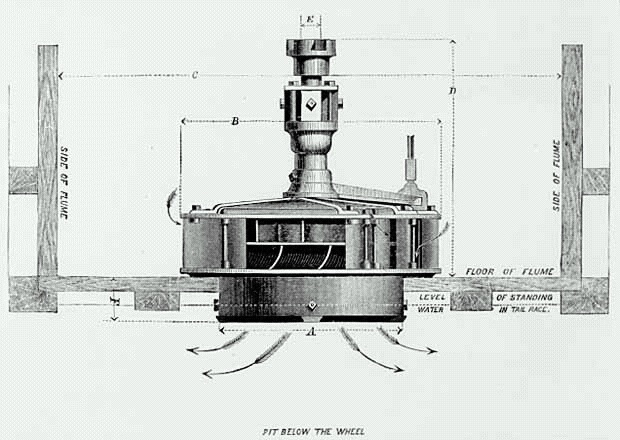

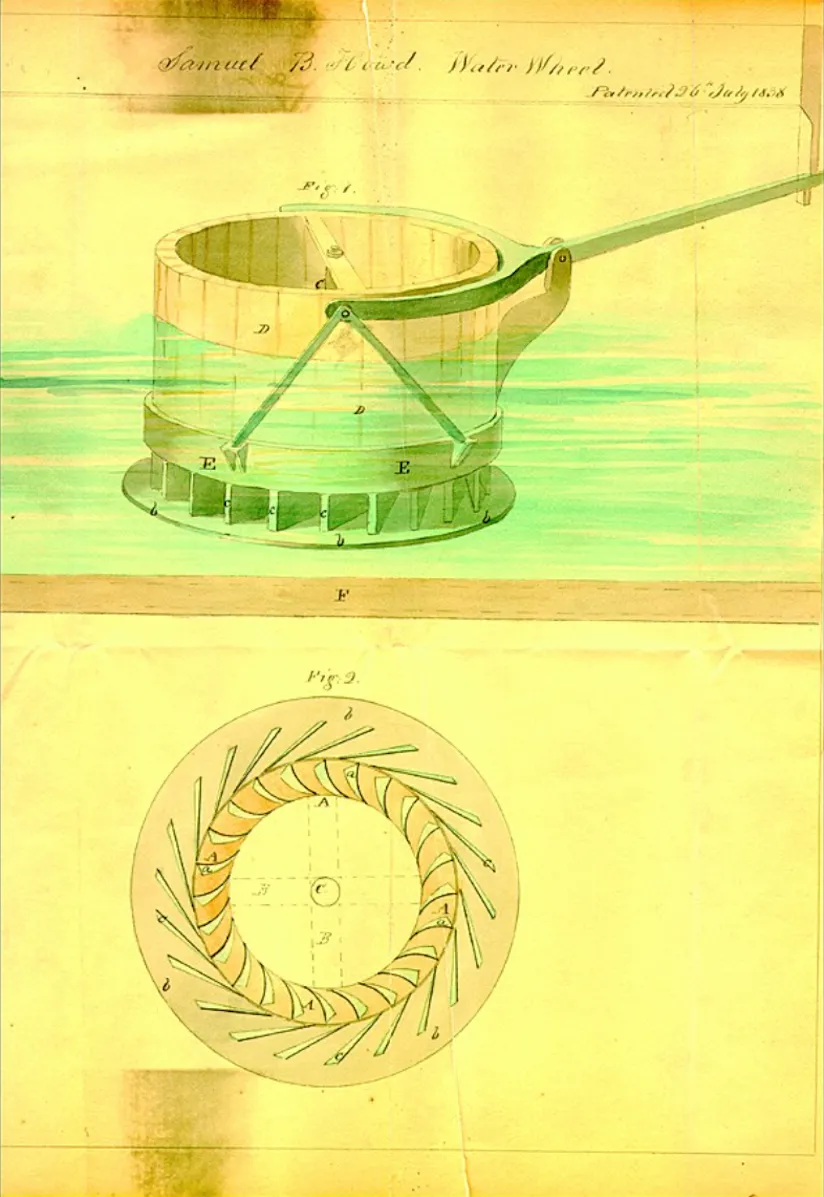

From that point, the water was directed via the flume underneath the road, then dropped several feet to the level of the turbine. By placing the turbine at the lowest point in the mill, the millers were able to utilize the water at its maximum velocity and maximum force to rotate the turbine blades. The water then discharged from the turbine through the tailrace, joining up with the river downstream, about 180 feet from the mill. The operation of a typical millrace, flume, and turbine of the nineteenth century is illustrated in Figure 8. The mill accommodates a Leffel 35-inch turbine, installed in 1893[2] (Figure 9). Solid information about the type of turbine(s) utilized in the mill prior to 1893 is lacking, but Samuel Howd’s 1838 patent of an inward flowing wheel had a big impact on turbine design in the northeastern United States, and the mill’s original turbine probably looked much as this one does (Figure 10).[3]

The mill interior is constructed of large oak hand-hewn beams extending the width of the building supporting the floor joists and flooring. The turbine, submerged in the flume, is cradled within a robust oak support called a Hurst frame, meant to withstand the vibration of the turbine and grist stones, and to act as a shock absorber to prevent damage to the mill structure. A complex array of shafts, gears, and pulleys actuated the machinery of the mill, transferring the energy generated by the turbine to the grist stones, corn hullers, elevators, and other mechanisms that produced flour and animal feed. The grinding stones, or grist stones, come in pairs, with the bottom one stationary and termed the bedstone. The upper stone, the runner stone, rotates on a spindle either directly connected to the main power shaft, or more commonly, driven by a secondary gear. Figure 11 shows a pair of stones leaning against the mill exterior. It is unclear whether these were used in this mill, or were simply gathered by past mill owners as spares. Notice that the stone is not one single piece, but composed of 19 individual pieces fitted together and enclosed by a metal strap. The use of multiple pieces allowed damaged stones to be repaired at far lower cost than replacing an entire stone. The cross-angled grooves carved on the stones permitted ground grain to move outward where it was collected and bagged or re-ground for finer meal. These grooves had to be periodically re-cut due to constant abrasion. Historically, the mill operated three pair, or three run, of stones simultaneously.[4]

Abram Shafer built the miller’s house in 1800.[5] This 1½-story, side-gable design consists of the original two-room wide, two-room deep cottage, plus a small, nineteenth century side addition, and a large rear section added in the twentieth century (Figures 12 and 13). The house, of post and beam construction, is clad with thin clapboard, the roof is sheathed in composition shingles that replaced the original slate. The exposed chimney back adjacent to the right door and behind the porch support, is a characteristic trait among late-Georgian frame houses in New Jersey, even as the small scale represents more of a vernacular form of worker dwelling.[6] The house is still occupied, despite periodic and sometimes devastating flooding by the river.

The floodplain behind the mill is highly productive, and has been cultivated or used as pasture for most of the past 250 years (Figure 14). These lands, originally owned by members of the Shafer and Wintermute families, are a mosaic of open fields, wood lots, and wetlands, and together with the river, village, and mill are part of a landscape that has changed little since the mid-nineteenth century, and in some respects not since the eighteenth century. The physical layout of the village of Stillwater, from the mill on the Paulinskill River, up along its single main street to the church at the opposite end, has much in common with the linear village forms of Rhineland Palatinate villages, or “dorfs.”[7] The essence of Stillwater as a historic locale lies in this largely 18th century German cultural form that was adapted to the American scene and which nurtured the activities of the village with the mill at its core. Much of the intrinsic character of its original settlement structure has been retained, in part due to Stillwater’s relative isolation from the urban centers, but also to a large degree because this pattern of settlement has worked so well to accommodate changes in the economic life of the community.

The Paulinskill River and its fertile limestone-enriched valley floor was the major draw of the early German-speakers to the Stillwater area. The river provided a well-watered bottomland for farming, but even more importantly, a source of power for mills. The first crude mill was constructed circa 1745 by Reverand Schaeffer’s grandfather and namesake, Casper Schaeffer, shortly after settling along the Paulinskill. It is considered to be the first mill built in Sussex County. By 1764, Schaeffer was eager to expand his operation and moved ¼-mile downstream where a permanent millseat was established.[8] It is at this spot that the present mill stands. Schaeffer subsequently opened a sawmill and oil mill utilizing power generated by the gristmill wheel.

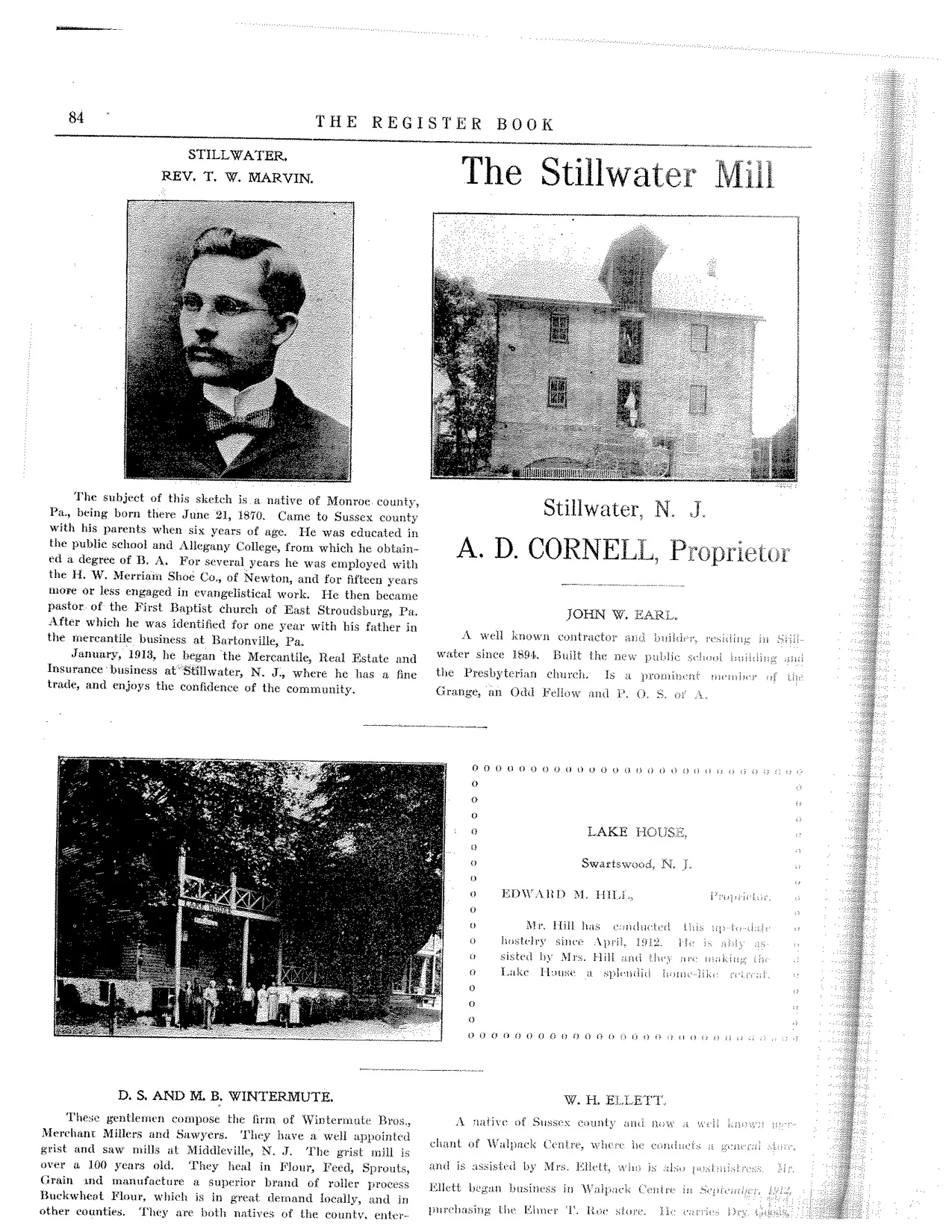

Five generations of Schaeffers operated the mill until William A. Shafer sold it in 1861 to Ralph Titus for $6,800.[9] It is reported in a county history from the late-nineteenth century that after great achievements, the Shafer clan suffered reversals of fortune as a result of failing to “…keep up the usual high standard.”[10] Titus seems to have ran the mill for several years before selling it to Martin Youmans in 1868 for $10,000,[11] yet Titus retained a financial interest in the mill until 1894 by holding mortgages from Youmans and then Henry Hopler, both of whom defaulted on their loans, reverting ownership of the mill back to Titus. Youmans operated the mill for 10 years, and Hopler for 14 years. In turn, Albert Cornell was miller until 1922 (Figure 15), Victor Hendershot through to 1926, and the final commercial operator was Joseph and Jane McCord.[12] After her husband was killed upon falling into the wheel pit in 1934, Jane McCord ran the mill with the help of her sons until ceasing business in 1954.[13] The Stillwater Mill was, by most accounts, the last commercially operated water-powered mill in New Jersey. A brief renaissance occurred in the 1970s when local farmers Willard Klemm and Augustus Roof purchased the mill, renovated the machinery, and ran it for demonstration and educational purposes. For a time, they processed grain from their farms and sold bags of flour to mill visitors. In 2000, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection purchased the mill, miller’s house, and property, transferring title to the New Jersey State Park System in 2006. Rental from the house goes toward a maintenance fund for the mill and house.

The mill visually anchors the village of Stillwater to the Paulinskill and the surrounding landscape, and embodies the historical feel of the community in large part because it has undergone so little change in its 163 years. As depicted around 1900, it is almost indistinguishable from its present appearance (Figure 16). The mill retains a very high level of integrity in terms of function, form, structure, and association. Though currently not operational, the mill historically has had only one function—to process grain into flour or feed. While Klemm and Roof installed some equipment scavenged from other mills and braced the flooring, the core of the mill, its Leffel turbine, dates to 1893, and the interior wood framing dates to 1844. One can detect a change in windows between circa 1900 and the present day (compare Figures 1 and 15), as the two-over-two appear to predate the six-over-six variety. The effect on the mill’s overall appearance, however, is slight. A little deterioration in the stucco finish is visible in Figure 3, although in sum, the mill is remarkably intact. A significant aspect of the integrity of form is the absence of retrofitting from a water wheel to a turbine—the mill was designed for turbine power. No outward modifications to the structure, aside from the windows, are apparent.

The headrace, judging from Figure 16, has suffered significant siltation or intentional filling, with the pond that is visible in the forefront of the 1900 photograph completely absent today except for a narrow ditch. The milldam upriver is in ruinous condition. The miller’s house has undergone significant alteration with the modern addition at the rear (Figure 12). This addition has nearly doubled the size of the house and radically altered the roofline and profile, although as seen from Main Street, this is manifested only as a slight upward cant to the roof.

II. Statement of Significance

Water-powered mills in rural areas were the catalyst for the industrial revolution in America, and they continued to dominate the economy and character of those places long after industry had become synonymous with fossil fuels and cities. By taking advantage of the kinetic energy of flowing water, the waterwheel was able to efficiently transfer work to machinery for grinding grains, sawing wood, processing wool, and a variety of useful tasks. In New Jersey, hundreds of mills were established on rivers and streams from the colonial period through the nineteenth century, and the watercourses on which they were located often functioned both as motive force and as transportation routes for their finished products.[14] Mills stimulated the growth of agricultural settlements and in turn thrived as the population grew. In Sussex County, New Jersey, gristmills played active roles in the development of the local communities by serving as incubators of commerce and industry. The Stillwater Grist Mill is a historically significant property as defined by the National Register’s Criterion A by representing various facets of the Era of Rural Commerce and Industry from 1844 to 1920. The mill is also significant under Criterion A for its demonstration of the theme of Sustainable Technology for the period 1844 to 1954, and illustrates the strengths and limitations of waterpower as a reliable energy source. Finally, the Stillwater Mill is eligible for listing on the National Register under Criterion C as an architecturally significant building and the work of a master builder.

The mill that was erected in 1844 was substantially different from the one that had burned to the ground in 1840; its walls were made entirely of stone, and its power mechanism was designed for a water turbine. The new mill, however, inhabited the same landscape, society, and local economy as the previous one, and as such it built on the patterns of rural commerce and industry that had been defined in Stillwater in the decades after the Revolutionary War. By 1816, Abram Shafer and his sons operated the gristmill, an oil mill, carding mill, blacksmith shop, distillery, and store,[15] providing employment for many in the village and connecting farmers, merchants, craftsmen, and laborers into a commercial network that extended beyond the boundaries of Stillwater. The 1844 mill inherited this commercial and industrial setting and continued to be the active center of the community.

Although profit margins for milling were historically thin, the mill generated cash flow from miller to farmer for raw grain, from miller to laborer in wages, and from merchant to miller for flour and feed. In 1860, William A. Shafer, with two hired hands, processed 22,500 bushels of grain (wheat, rye, corn, buckwheat, and oats) and produced 550,000 lbs. of oat feed and 566,500 lbs. of flour.[16] After paying his hands $40 per month each, Shafer turned a profit of about $3,500. This appears to be a substantial amount for the period but was comparable with the production yield and profits of James Butler, another local miller. The 1870 census shows Martin Youmans processing 25,000 bushels of grains but just breaking even.[17] By 1880, miller Henry Hopler processed only 12,900 bushels of grains, yielding him a net income of about $570, after paying his hired hand 75 cents a day.[18] This was the beginning of the period in which gristmills were moving to urban areas, as steam overcame water as the preferred power source, allowing owners to situate mills closer to major transportation routes, such as railroads and ports, and thus lowering their costs. Although enumerations of the products and value for the Stillwater Mill are not available past 1880, the decline in bushels between 1870 and 1880 quite likely represents the start of a long-term trend that ended with Jane McCord’s shutting of the mill in 1954. The importance of the mill to the economic life of the village of Stillwater cannot be overestimated. As regional and national economic changes were occurring that narrowed the scale of the mill’s business, so too was Stillwater’s population shrinking, by 15 percent in the 1880s and by another 15 percent in the 1890s.[19] By 1940, there were only 678 people in the township, nearly 1,000 less than there had been in 1870. Clearly the declines in milling and agricultural activities went hand in hand with the population decline. In terms of the theme of Rural Commerce and Industry, the mill’s significant period of contribution to the community can be considered from 1844 to 1920, when motorized transport began to significantly lessen the demand for local gristmills.

The Stillwater Mill further contributes to the broader patterns of American history through the theme of Sustainable Technology. The late 1830s introduced the notion of Manifest Destiny to Americans, a philosophy built on the dual premise of American moral and technological superiority and the unlimited supply of natural resources on this continent. These ideas led inexorably to the terrific expansion of extractive industries that moved westward with the early waves of settlement, depleting forests, mountainsides, and wild game for lumber, ores, and hides. Though usually associated with the modern Ecology Movement that dawned in the early 1970s, the idea of sustainable technology is one that has deep roots in the American consciousness and can be traced to Jefferson’s ideas about the yeoman farmer, Thoreau’s writings on the moral value of the countryside, and Emerson’s essays on self-reliance. These notions resonated with people in the development of the water turbine, which was first introduced around 1840. The Stillwater Mill may have been one of the first mills in New Jersey to be designed and constructed specifically for turbine power. Here was an inexpensive mechanism, occupying less space than a waterwheel, easier to maintain, and achieving higher velocity, that proved essential in sustaining many small rural mills through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By 1899, only 15 percent of all manufacturing power was produced by waterpower in the United States,[20] marginalizing those waterpowered mills that remained and making survival a matter of demonstrated efficiency. The Leffel-type turbine installed in 1893 had a rated efficiency around 90 percent, far exceeding steam engines of the day.[21] By this means, the Stillwater Mill was able to remain profitable even as its importance to the local economy declined.

The fire that destroyed the predecessor mill in 1840 may be thought of as fortuitous, as it permitted Rev. Casper Shafer to construct a wholly new structure that was designed to accommodate this new power technology, the turbine. The nearby Hunt’s Mill in Fredon did not incorporate an interior turbine until 1886, and Keen’s Mill in Swartswood did not until 1903. Much structural alteration of those mills was necessary to remove the exterior water wheels and install the turbines, and in the case of Keen’s Mill, the retrofit was not totally successful as vibrations from the new turbine caused damage to the mill structure. When a new turbine was installed in the Stillwater Mill in 1893, it was a fairly simple process of replacement rather than modification. That replacement turbine survived intact through the operational life of the mill, and remains there still. Under the theme of Sustainable Technology, the Stillwater Mill’s period of significance was 1844 to 1954.

The Stillwater Grist Mill is an outstanding example of a mill building that exhibits the creative work of a master builder at the peak of his talents. Most nineteenth century stone mills are interesting because of the balance they achieve between the weightiness of the stone and the verticality of the building. They resemble ancient castles in this respect. All were built to be functional and durable, and many show a highly developed technical mastery of the medium. But few exhibit the scope of architectural expressiveness developing from a combination of scale, materials, and composition exhibited by the Stillwater Mill. The exquisite stonework of the lower story contrasts wonderfully with the stucco finish of the upper stories, which then transitions back to stone with the dark slate of the roof. The rear elevation, in particular, is a picture of grace, with the vertical symmetry of the windows and door alternating with the horizontal bands of limestone, stucco, and slate, and in the lower right corner the raceway arch adding a coda to the rhythm of the entire pattern (Figure 5). The recessed doorways, front and rear, complement the composition of the walls by introducing depth to the flat surfaces.

It is almost irrelevant whether the builder thought of the mill in these terms. The limestone was used because it was locally available and created a solid foundation; the stucco provided an impermeable coating for the upper stories; the doorways were recessed to create a better internal seal against cold, wind, and rain. These were traditional solutions to design problems undertaken by individuals who were supremely confident in their abilities to create a structure that would perform to the specifications demanded to sustain a profitable milling business. There is practically nothing of the mill that is decorative or ornamental, yet the builder has achieved a highly sophisticated structure that demands one’s attention. It stands at the opposite end of Main Street from the white steepled church and together they form bookends of the town, with one end devoted to spiritual nourishment and the other end to productive nourishment. Seen from this perspective it is not surprising that both church and mill represent the most important architectural buildings in the community.

The Stillwater Grist Mill and its associated elements of miller’s house and raceway, satisfies the National Register’s Criterion A under the theme of Rural Commerce and Industry by its significant contribution to the community as the nexus of the local economy for the period 1844 to 1920. In this capacity, the mill stimulated the growth of the village of Stillwater and remained the most important commercial and industrial enterprise in the area.

The mill also meets the test of significance under Criterion A through the theme of Sustainable Technology. By the early introduction of an efficient, low-cost water turbine, the mill demonstrated its capacity to endure extremes of weather, economic downturns, and a declining local population base. The installation of an advanced replacement turbine in 1893 sustained the mill for another six decades in spite of the challenges for a small rural enterprise. The period of significance under the theme of Sustainable Technology is 1844 to 1954.

Finally, the mill is an important example of nineteenth century architectural design and mastery of the building trade, and meets the National Register’s threshold of significance under Criterion C. The Stillwater Mill is an eye-catching building that retains a high level of structural, functional, and associational integrity, and remains the centerpiece of the historic village of Stillwater, New Jersey.

(All photos by author)

Footnotes

[1] Casper Schaeffer, Memoirs and Reminiscences together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, NJ: privately printed, 1907 [reprint, Harmony, NJ: Historical Society of Stillwater Township, 1984]), p. 32.

[2] Augustus Roof, Stillwater resident and former owner of the mill, personal communication, April 29, 2007.

[3] Daniel W. Mead, Water Power Engineering: The Theory, Investigation and Development of Water Powers. (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1908), p. 11.

[4] U.S. Census, 1880. Schedule 7, “Products of Industry in Stillwater Township in the County of Sussex, State of New Jersey.”

[5] The Shafers variously spelled their name ‘Schaeffer,’ ‘Shafer,’ and ‘Shaver.’

[6] Henry Glassie, “Eighteenth-Century Cultural Process in Delaware Valley Folk Building,” in Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture, edited by Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1986), p. 410.

[7] Thomas E. Jones, The Rural Historic Landscape of the Stillwater Village Area, prepared for the Proposed Reconstruction of County Bridge S-01 by Sussex County, New Jersey, 2002, p. 7.

[8] Schaeffer 1907, 30-31.

[9] Sussex County (NJ) Deeds, Book A5, Page 180, January 11, 1861. On file at the Sussex County Clerk’s Office.

[10] James P. Snell, History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881) 387.

[11] Sussex County (NJ) Deeds, Book S5, Page 104, March 30, 1868. On file at the Sussex County Clerk’s Office.

[12] Sussex County (NJ) Deeds, various.

[13] Jeanne Edsall, “Mill wheels turn again along the Paulinskill,” New Jersey Sunday Herald, June 4, 1972.

[14] By 1751 there were already 246 gristmills and 185 sawmills in the province of New Jersey. Peter O. Wacker, “The New Jersey Tax-Ratable List of 1751,” New Jersey History, 107:33 (1989).

[15] Snell, ibid.

[16] U.S. Census, 1860, Schedule 5, “Products of Industry in the Township of Stillwater, County of Sussex, New Jersey.”

[17] U.S. Census, 1870, Schedule 4, “Products of Industry in the Township of Stillwater, County of Sussex, New Jersey.”

[18] U.S. Census, 1880, Schedule 7, “Products of Industry in the Township of Stillwater, County of Sussex, New Jersey.”

[19] Compendium of Censuses, State of New Jersey, 1726-1905. (Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy Publishing Co., 1906), 37.

[20] Robert A. Howard, “Primer on Water Turbines,” Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, 1976, 8:53.

[21] Carl M. Becker, “James Leffel: Double Turbine Water Wheel Inventor,” Ohio History, 75:201 (1967).